RENATE BERTLMANN

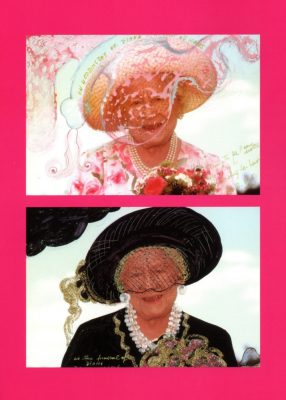

Since the early 1970’s, “Amo ergo sum” has been the maxim of Renate Bertlmann’s artistic investigation of the timeless and provocative relationship of tension between Eros and Thanatos. In the sensitive border-zone between kitsch, art and taboo, her diverse creations celebrate the trivial myths of desire and research the ironic, utopian, and pornographic aspects of sexual love. In opulent, plastic and picturesque settings, which are analyzed with film and photography in a second work sequence, the artist visualizes the attraction of opposites and takes aspects of gender differences into consideration. Immediately touching pictures describe the power of desire as well as feelings of shame, and discover the sensual fascination which can express intimacy as well as distance.

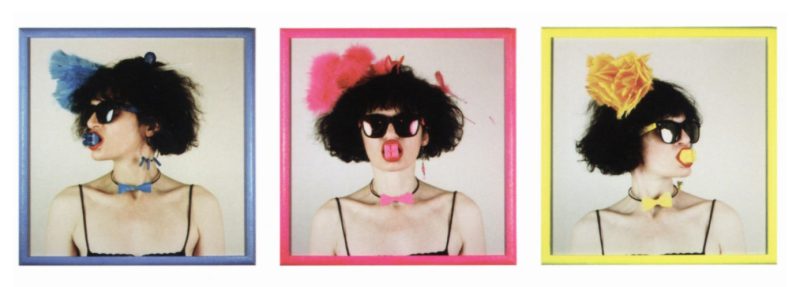

As clearly as the artistic interest is formulated, the iconography with which exemplary aspects of gender differences are hypostatized appears as diverse. Impressed by the feminine discourse concerning feminine role models and the individual need for space from attacks of reality, symbols of utopian, egalitarian love dominate in her early work. In the sequence, “Zaertliche Beruehrung” (Gentle Touch), two contrasting- colored latex pacifiers explore the different stages of intimacy. The two equal cast members rub against each other uninhibitedly, wrap around and penetrate each other in an unmistakable representation of a sexual encounter. “Ex Voto,” a sculpture of the late 1980’s, is substantially more aggressive: feminine breasts, promising nourishment and care put forth an unexpected destructive quality. A sharp knife points out from a nipple of the heart-shaped styrofoam torso, presented like a valuable in a glass aquarium. The object of desire, the female body no longer signals vulnerability, but threatens injury, suddenly demands a respectful distance. The compositions of the past decade are dominated by a rather ironic gaze, preferably falling on the erect phallus appearing in the most unlikely costumes. A devotional is dedicated to “San Erectus” with glamour and glitter. Lavish, tailor-cut ladies’ robes decorate a group of colorful dildos, “les enfants terrible,” who have come together for an absurd fashion show. Seeking shelter underneath a glass bell with “Cheese from Austria” embossed on it, the seven dwarfs are dressed splendidly in their long pointed red caps. The cardinals bedded in silk and satin (from the computer animated sequence, “Zwitscher Litanei” [Chirping Litany]) prove that spiritual vestments suit the upright fellow very well. Depictions of the male organ no longer shock; they are rather appreciated as pleasure-bringing mediums. For Renate Bertlmann they are an ambiguous subject, which degenerate to toys under the glass lintel. “[All that remains of Eros’ elemental force are infantile fantasies which should be protected rather than destroyed]” (Konrad Paul Liessman)

The facet-rich work of the artist, who appreciates classical display methods as much as experiments with non-artistic media and materials, is formally penetrated by her explicitly photographic view of reality. All her works are of ephemeral nature, as performances, installations, or even conventional artworks are; they behave as raw material to an additional photographic setting. In countless individual pictures, Renate Bertlmann captures the sensory certainty of her existence onto celluloid and squeezes the last detail out of the photographs. This is how in over three decades, a truly monumental archive from which individual motives were isolated and programmatically condensed into cycles, sequences and series, and of recent, assembled into electronically generated picture sequences, came into existence. These ensembles obtain a completely independent significance within the context of the entire work. On one hand they tell the new story, not necessarily inherent in the work as accused, and on the other hand shift the act of aesthetic reflection to a meta-level. The camera creates a safe distance between the image object and the seeing eye, objectifying the conflict with socio-political problems in the context of the artwork as a whole. Suddenly artistic strategies of embodying immediate work on the subject are comparable to those which society demands of the individual. They appear as fake and as determined as that painful ritual to which body and soul are willfully servant. That defuses the explosive nature of the central theme and defers to the author, who questions herself in her photos: By consistently refusing the concretization of desire in every inner vision, she keeps the promise which every art possesses in balance. What remains is curiosity for reality, together with the hope for change.

Edith Almhofer

Gumpoldskirchen, in May 2002