Opening: Monday, 13 March, 7 p.m.

Introduction: Julian Tapprich and Margaret Dearing

sponsored by: BKA-Sektion II; MA7-Kultur; Cyberlab; Austrian Culture Forum, Paris; Institut Français Autriche, Vienna

Two artist collectives, the Association Jeune Création in Paris and the FOTOGALERIE WIEN, both institutions, that have been active for decades in encouraging and supporting contemporary art, have developed a collaborative exhibition project in the field of tension generated by photography and other mediums. The exhibition, which was shown in the Jeune Création gallery in Paris at the beginning of November 2016, will now be presented in an expanded form in the FOTOGALERIE WIEN. Project organisation: Michael Michlmayr, Julian Tapprich (FOTOGALERIE WIEN), Margaret Dearing and Edwin Fauthoux-Kresser (Jeune Création).

On the basis of the work of five artists who live in Paris and Vienna, the exhibition is an invitation to discover how photography penetrates the permeable borders of individual mediums and becomes part of the work material. Here, drawings, video and sculpture appear to be steeped in photographic images both in their materiality and in respect of the work processes and conceptual background too. The artists draw on photographic iconography for these fragmentary re-orderings – whether as archaic weaving, video animation, inlay work, transposing a flat print into three dimensions or reproducing it using charcoal drawing. For each of them the challenge seems to be to create new spaces that make it possible to render visible the connections of heterogeneous and differing pictorial material. Again and again the gaze bumps into these idiosyncratic configurations. The interventions in the image are visible everywhere and it rapidly becomes clear that the visual synthesis is only a fiction, a utopia. Each break in the material or perspective parades the irritation of the experimental mixture before our eyes that much more insistently and reveals the limitations on creating a unified whole. The different approaches taken by the artists in which photographs perpetually shine through calls specific characteristics of the medium into question: the motionlessness, the rigid point of view, the flatness, the limits of the picture. These lead to formulating questions that are wider than photography. How does one keep together what the image delivers in separate parts? How does one master the challenge of a defragmentation of the world?

Among other work Brigitte Konyen is showing the photo-weave Geschenkbild (Me, Myself and Them). The work is a self-portrait for which the first photo that Konyen made of her mother in 1971 when she was still a little girl serves as a thematic parenthesis. At that time each print that was ordered came with a small complimentary copy – a so-called ‘free gift’ picture – and this doubling up, this combination of large alongside small has always exerted a certain charm on the artist. For her photo-weave images the photograph is both starting point and work material. Personal photos, but photographically reproduced drawings and texts too are processed into art material by being woven. They appear in the grid of the image surface as little set pieces of memory, snapshots from Konyen’s life. Due to the two levels created by weaving the images overlap one another: details emerge showing us a familiar photographic reality in the abstract structure. Then again, other things are concealed and making associations is left up to the viewer. Time and place dissolve into self-made order. In general, her photo-weave works can be seen as a statement about the legibility of photography and how memories are constituted.

In Claudia Larcher’s work Heim [Home], one of the video works which she is presenting in the exhibition, a house is viewed from attic to cellar: Advent garland, leather suite, chandelier, printed curtains, a lawn mower that putters by the window, electric drill, screwdriver – the entire reservoir of a petit bourgeois provincial idyll, a well-lit icy absence of people. The work consists of a video animation in which still and moving images are edited into an apparently endless panoramic pan underpinned by an uneasy, droning soundtrack. This brings the uncanny up to the surface of the quotidian. Far distant from any rational sense the banality of evil is manifest in codes and allusions at the edge of perception and conveys a feeling of utter homelessness. Rooms have a distorted perspective and are bizarrely edited into each other. Sequences aspire to a chronology that consists only of snapshots, flashes of experience with no causal connection. (Thomas Mießgang)

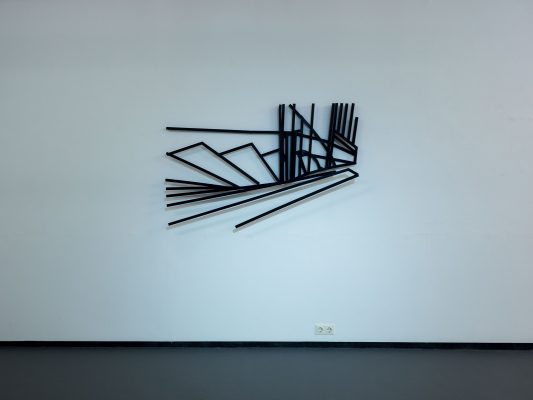

The photo collage, The Great Train Robbery – A Little Journey Through Film History, by Klaus Pamminger, uses fragments from genre films of the whole of the twentieth century. These form the railway telegraph office from the first scene of Edwin S. Porter’s Western, “The Great Train Robbery“, one of the first films from the early history of cinema if not the very first ‘real’ film. What Edwin S. Porter developed in 1903 is to be found in all subsequent feature films. In Pamminger’s work, Fleming’s “Gone with the Wind“ together with Hitchcock, Buñuel, Kubrick and others right on up to Tarantino/Stone’s “Natural born Killers“, turn in a chronological spiral in the room. What always fascinates Pamminger with the inlay-like photo works is – in addition to the fundamental concerns with space and spatial perception in differing contexts – that as in painting, the production process leaves him almost completely free to compose an image. However, it is only the eye that determines the application of colour and brushstroke, by the selection of a particular section (here composed of filmic frames which, wherever possible, were manipulated no further). Space-time but also the substantive reference levels are taken into account equally and images are produced which, in their interaction, allow us to look outside the ‘spatial box’ and tell multiple stories simultaneously.

Timothée Schelstraete is showing charcoal drawings and paintings which are based on a collection of photos he made – literally snapshots, photos he discovered in the internet, in books or albums, film sequences … They reflect the directly or indirectly fragmentary relationship he has to his surroundings and are the result of a kind of permanently floating attention. A subject comes up, the image attracts his attention, hypnotises him and then leads him on to another. Formal or semantic associations determine the work as if fixating on one thing too long and without sufficient reason had imbued it with meaning – without him intending to anything other than laying out some bait. By randomly linking fragments of the world he captures or creates with each other he obtains a kind of atlas, a constellation of motifs that follow an arbitrary chain of logic.

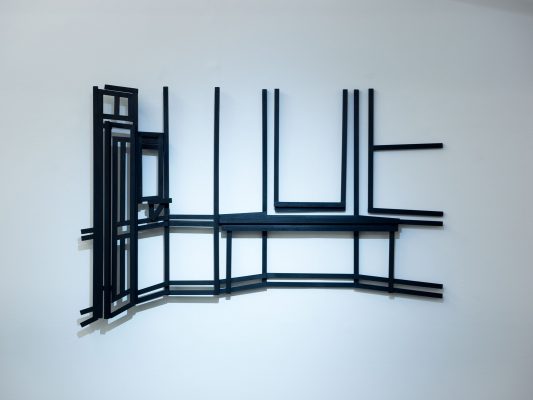

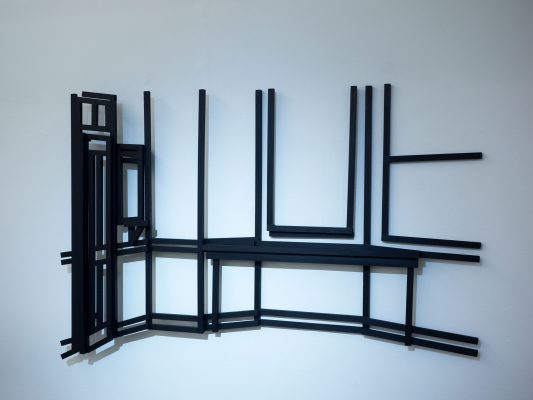

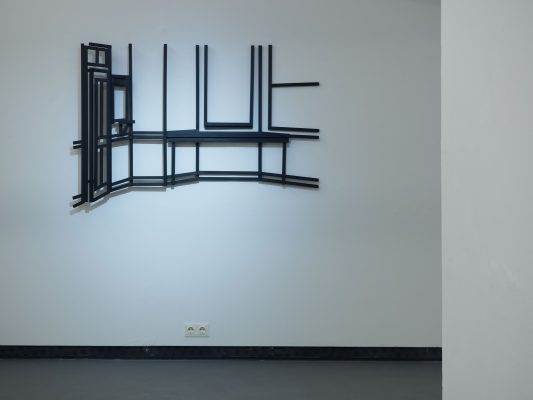

Beatriz Toledo has developed a process of creating art works that ascribes an expanded meaning to the photographic image and situates it in a wider context (photograph on wallpaper on wooden construction). Starting from the assumption that photography is a means of surveying and recording reality, Toledo brings into play sculpture and installation too, sounding out the boundaries between spatial parameters such as area and volume. The artist finds points of departure for her work in her everyday surroundings (views of her studio, press cuttings, found objects etc.): the pictures are deconstructed and reconfigured in space. In this systematic work which undermines the status of photographs and their integrity, the artist shows new stories and possibilities of interpretation. The resulting installations playing with overlapping, irritation and deception are thereby directly concerned with issues related to the materiality of the images. (Yannick Langlois)

Edwin Fauthoux-Kresser and Petra Noll, for the collective