Opening: Monday, 12 March, 7 p.m.

Introduction: Katharina Manojlović

sponsored by: BKA Kunst; MA7-Kultur; Cyberlab; thanks to: Anja Manfredi, Mihai Şovăială, Miha Colner, Lisl Ponger and Gabriele Rothemann

Dadaist and poet Tristan Tzara called the invention of the collage the most revolutionary moment in the development of painting and meant by that the fundamental break with established forms of artistic representation that it symbolised. Implicit to the technical processes of what comprises collage — gluing (Fr. coller), scratching, cutting, tearing, folding, mounting, assembling and de-composing etc. is the potential for radicality. While the papiers collés of the Cubists drew their sustenance from used, discarded and apparently banal sources, we are surrounded today with multiply reproduced, re-formatted and re-edited copies of constantly accumulating digital debris. The current focus of the Fotogalerie Wien will present four exhibitions and includes a wide spectrum of methods and processes used in collage in contemporary photo and video art. This renders the narrative and autopoietic strengths of this art form visible along with its innovatory energy as one of its fundamental and most evident characteristics, especially in relation to new technologies or spatial and sculptural expansions. The drift of the images is also always guided by energies that are anarchistic, driven by chance and play.

The focus of the third show of the 2017/18 special topic consists of works which take up a specific subject area or motif and place it at the centre of a process of reflection. This makes clear how collage has the ability to render the familiar unfamiliar and so to compress reality that what is beyond depiction and representation and outside habitual ways of seeing is rendered visible. Domains are created that follow their own rules; visual constellations remain abstract while simultaneously unfolding their documentary character through their explicit references to reality, picking up the pre-existing, bearing witness. Their critical potential derives in no small way from the fact that they draw on reality in order to dissect it, to draw over and displace it. And so they show things as they never were but yet as they really are. Artistic deconstruction, the alienating appropriation of found image material and its mechanisms, lays open how images function and the ideologies that are transported through them.

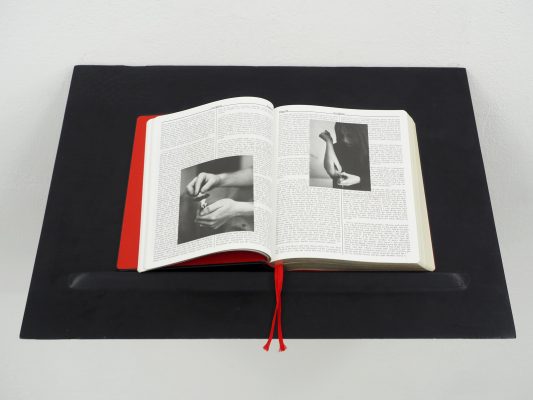

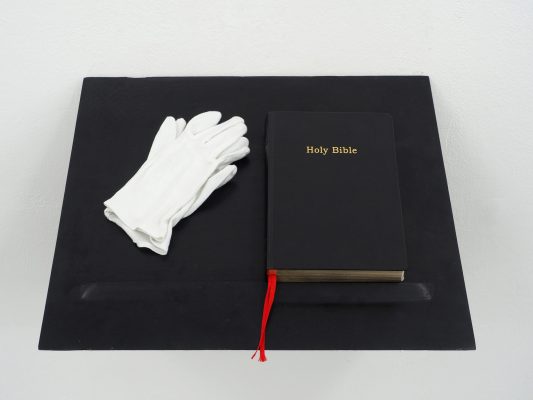

The artist book, Holy Bible (2013), by Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin, published by MACK and the Archive of Modern Conflict in London, is bound in black leather with its title stamped in gold. The presentation suggests an antiquarian edition of the bible and, in fact, it is an exact reproduction of the King James Bible (1604–1611) but supplemented by photographs relating to war and violence from the Archive of Modern Conflict. These are superimposed on the text and vaguely refer to passages marked in red. The artist duo examines how violence is visually manifested, influenced by the hypothesis of Israeli philosopher Adi Ophir, that God is predominantly revealed through catastrophes. Holy Bible can be read as a continuation of their artist book, War Primer II (2011), which was inspired by Bertold Brecht’s Kriegsfibel (1955), in which the author combined newspaper cuttings about the Second World War with his own poems.

In Tanja Deman’s video installation, Abode of Vacancy (2011), modernist architecture as both concept and utopia takes centre stage – a ‘non-narrative fiction’ (Deman) that the artist has constructed from a series of tableaux. Her interest lies in the spatial experience and collective memory and perception of (inherited) architectural structures. Subtle movements subvert the initial impression that we are dealing with still images; they are part of the staging and illusion of an autonomous building. Deman’s composition of the takes allows us to immerse ourselves in empty buildings and desert landscapes. In fact, we are dealing with stretches of coastal landscapes in Croatia and the Netherlands. Emptiness as a shelter or dwelling – one way of reading the title of the video. This makes the movements in nature all the more emphatic: of trees in the wind, of shadows …

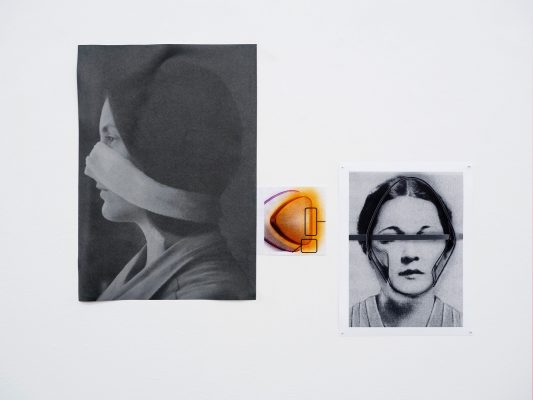

Bernhard Hosa, in his series, Auf der Suche nach dem richtigen Bild (2012), examines historical images and the role of photography as a tool of discipline. Using the methods developed by the French criminologist and anthropologist, Alphonse Bertillon (1853–1914), the new medium was profitably employed for identifying people on the basis of their body measurments (Bertillonage). The assumption that the character and identity of a person could be determined by the measurment of physical features was not far off. Hosa deconstructs the reproduced portraits – ‘mugshots’ – by folding them and reconstructing them anew. The staples that hold the edges of the pictures together are reminiscent of parts of the body that have been operated on or autopsied: these fragmentary, dismembered faces appear monstrous. What in the original picture serves to identify a type, to define and, in the end, to stigmatise the ‘subject’, disappears.

In Petra Jansová’s series, Andere Dimensionen der Schönheit (2015) the core is provided by ideal beauty and the measures to be adopted to achieve it as propagated in (historical) cosmetic industry images. Some of the works being shown are like still lifes, arrangements that talk of transience – always, runs the title of one of the works – and quote historical vanitas motifs. The conserved moisture in the picture reminds one of the promises of moisturising cream and talks of fears of decline and dessication. Much of it conveys a mask-like impression, the face at the centre is a palimpsest to be washed, scraped, creamed and rubbed. The rendering visible of other pictorial levels such as the raterisation of the reproduced advertising subject and the selection of cropped sections allow what is depicted to tip over into the surreal – rituals and gestures become mysterious. Viewing Petra Jansová´s finishing touches of the (photographic) objects also recalibrates our perception.

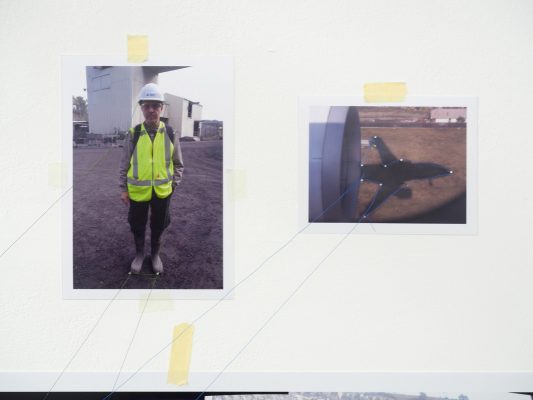

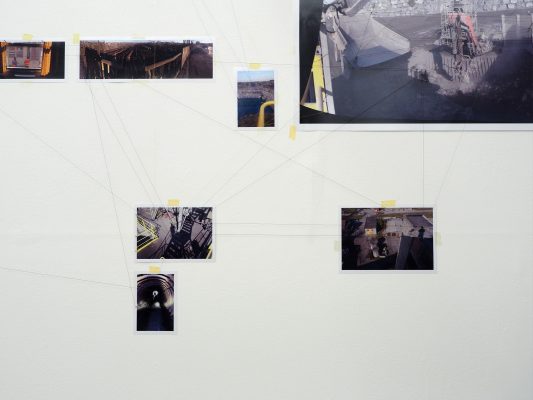

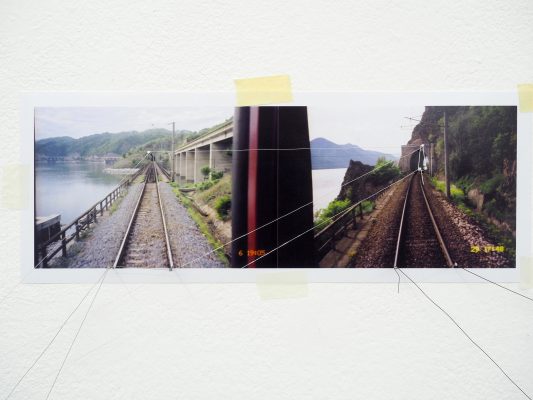

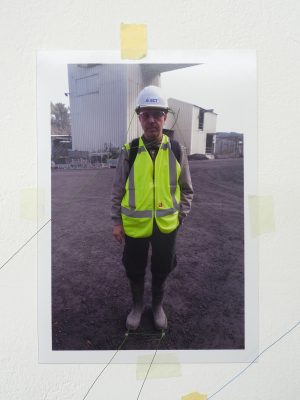

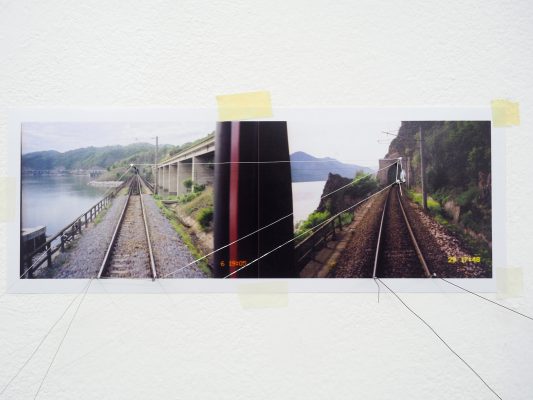

Iosif Király’s works examine the relationship between space, time, perception and memory – as is the case with the Reconstructions project begun in 2000 – and ‘draw attention to the linkages and synchronicity that can, at times, occur between humans, things and events.’ (Kiraly) The means employed here have something provisional about them. There are connective lines which, when followed, do not necessarily lead to unequivocal results but do raise questions, open up imaginative spaces and show that things remembered are not as easily defined as photography might suggest. For example, how do personal and collective memories fit together? Was something different here, and for whom? Even the panoramic view offers only a section of a particular perspective and in the end proves to be an illusion.

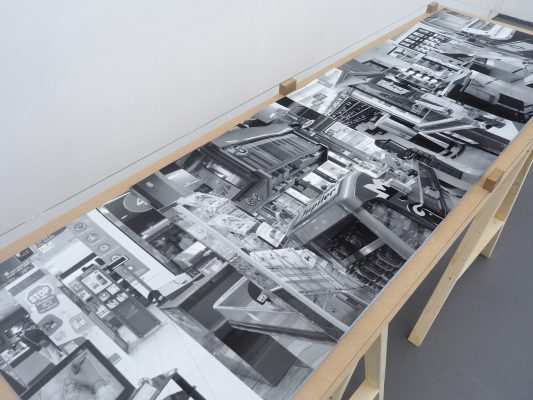

Stephanie Kiwitt is interested in everyday urban life, its qualities and structures but, in particular, the architectures of places concerned with contemporary consumer culture and its commodity fetishism. In the book project, Capital Decor (2011) – a 12.73 metre-long fold-out – she examines the spatial and formal language of discount stores using a chain of abutted interior views of supermarkets. For the artist this is a ‘photographic picture space with the greatest amount of pictorial density which generates an artificial order at the same time’. End and beginning merge; architecture, advertising language and packing design are transformed into an endless loop, in a highly compressed space. The preparation of the photographic material, its harmonisation through the use of black and white and the rasterisation lend it a uniform rhythm and a monotony that is further accentuated in the sound work that accompanies the book object. For this purpose Kiwitt noted the fragments of writing in the photographs – slogans, product names, etc. – and had a speaker read them.

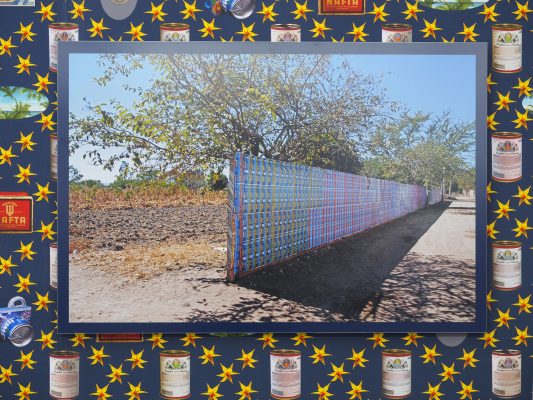

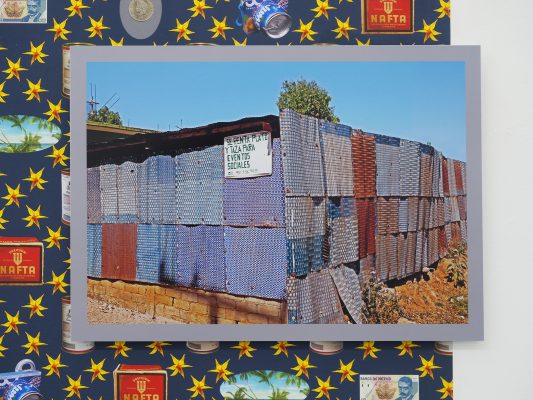

The point of departure for Tim Sharp’s photo installation, Capital Offence (2014/2018), is the precarious condition of traditional agriculture in the context of neo-liberal upheavals and the threats implicit in the NAFTA (free trade) agreement and on-going global land appropriation. The works depict enclosures made by farmers in rural areas of Southern Mexico using tin can blanks to mark out their small communally-owned parcels of land: a clash between agro-industry and ‚Campesinos’. Sharp does not understand Capital Offence as a ‘statement but as the visual realisation of a discursive net with multiple nodes and strings of association’. The artist-designed wallpaper, the background to the framed photos, continues with motifs related to the food industry – icons of consumer culture, industrial production as well as political resistance segue once again into architecture. The reference to the historical democratisation process in the decoration of living space that once gave the middle and working class wallpaper now evokes the ambivalence of globalised economy.

(textual support: Katharina Manojlović)