Opening: Monday, 4 April, 7 p.m.

Introduction: Petra Noll

sponsored by: BKA Kunst; MA7-Kultur; Cyberlab, Michael Sprachmann/Fine Art Printing and Framing, Vienna; Rahmen Mitter, Vienna

thanks to: Schule Friedl Kubelka für künstlerische Photographie, Vienna; Cultural Endowement of Estonia

Engaging with the past, with its images, evidence, architectures and contemporary witnesses stimulates “afterimages” in the mind. Elapsed time makes another view of what lies in the past, one’s own identity and origins possible. The primary concern in this exhibition are artists’ visualisations of memories that are linked to subjectively experienced places or sites which have been charged by collective emotions. Research into one’s homeland, travelling shots through deserted rooms, archive pictures of personal experiences, places and persons and/or appropriated photographs of historically significant locations are placed in the context of contemporary images, statements and forms of representation such as sound/music, movement or are transformed by re-working them. Alongside working through or depicting personal inner processes, the artists also consider the question of how memories change the perception of reality. Equally, this concerns time which, in memory, articulates as the link between the present and the past as well as the significance and informational value of photographic and filmic images in the process of remembering.

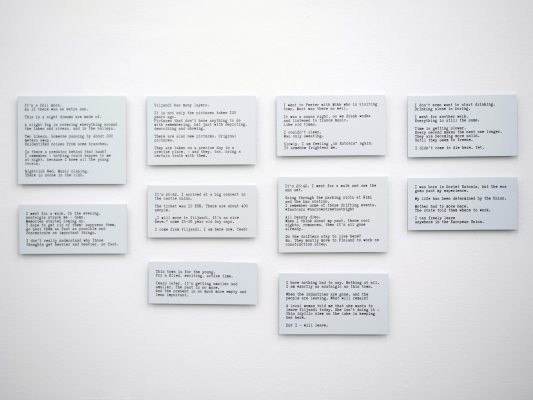

Madis Luik’s installative, multimedia memory work, Linn: Viljandi/Stadt: Viljandi (2014) is about the city of his childhood, the Estonian city of Viljandi. It connects up three formal levels: photographs of street scenes and architecture, bearing witness to the historical/political change, texts relating to his personal thoughts about his city. The work also includes the documentary video, Elmo, in which he carries on a conversation with Elmo Riig, a well-known Viljandi journalist who has worked for the local newspaper, “Sakala”, for 18 years photographically documenting the most important local events. During a number of car journeys that make up one of Elmo’s working days they talk, in particular, about his work and the medium of photography. The three-part work, formally constructed from the interweavings of references to texts, photos and videos in newspaper and online articles, was made during a 90-day stay of the artist in Viljandi. All three parts are concerned with issues of the architecture, history and future of the city which has been marked by a great deal of emigration. Although all parts are representative depictions of the city, they achieve a comprehensible narrative level only when they all work together.

Sissa Micheli is showing the video Rue de la Tour – The History of a House in 8 Chapters (2009/2016). Based on the documentation of the Parisian villa in which she grew up, a young woman describes her family. Celia tells of her childhood, four siblings, the failed marriage of her parents and her life without her father who only ever came as far as the doorstep of the house. The slow travelling shot through the rooms chosen by Sissa Micheli visually conveys the mental process of remembering: The quiet flow of images as if from the subconscious is concretised by Celia’s voice and becomes a palpable current of experiences. Images and voice meld into a labyrinth of memories. The video is the third in a trilogy about living spaces that are just short of disintegration. In this series Sissa Micheli examines, in a very poetic and emotional way, how homes can awaken and store memories. Starting from Celia’s account she goes on to talk about general existential issues and feelings such as love, security and loss.

In the video, Revisting past (2015/2016), Michael Michlmayr is concerned with the photographic image as a stimulant for subjective memory. He took negative strips from his archive of black-and-white images from 1981–2000 into his hands for a short time, turned them over, looked at them and photographed this act. These photographs were then edited together into a film, thus creating a picture-in-picture situation that takes the act of looking as its subject. In the background there are the regular clicks of a camera shutter release suggesting authenticity. Even very short visual stimulation is enough to prompt memories of the artist’s own life story, important persons, places and events, of previous art works and social and political events. For the viewer it remains an associative pictorial journey in which unequivocal visibility is denied because of the filmic re-contextualisation, the speed of the images, the superimpositions and turning of the strips as well as the lack of familiarity with the contents. It concerns engaging with seeing/not seeing, the structures of perception and the informational content of photographic images.

Anna Mitterer’s film, Sonate (Hommage à Vinteuil) from 2008 shows a travelling shot through a continuously changing room and thus consistently provokes new relationships to reality. The pictorial language is derived from a piece of music: Mitterer asked Viennese composer Alexander Wagendristel to compose a new piece based on the violin sonata by the fictional composer, Vinteuil, that only exists as a description by Marcel Proust in “Swann in Love” and is thus equally fictional. In Proust’s work, listening to Vinteuil’s music not only brings Charles Swann to think of his past, unhappy love, Odette, but also leads him to the awareness of an invisible reality. Sonate depicts the infinitesimal moment in which an analogy between the past and the present happens. The act of remembering is reflected in the movement of the camera through the ever-changing room. Above all, it deals with the description of a mental process, the instant of intuitive memory, but also the inner process of how the reception of an art work that makes use of images and sound can be reflected on.

Bärbel Praun is showing the work, this must be the place (2015), a personal research about place, space and perception and an examination of the notion of “home”. She presents all the pages of a book with black-and-white and colour photographs as a wall work. In the main they deal with landscape subjects e.g. the Swiss mountains, where she lived for a time. The enlarged sections mark her closeness, her involvement with the natural world. They are predominantly very abstract, open images with a symbolic and associative character. The concentration can be felt, the detailed observation – of her own snowflake-catching hands for instance – the very sensitive approach and the artist’s fascination with the beauty of surfaces and structures. Having never lived in the same place for more than a few months at a time over the last few years, she is moved by questions as to the meaning of home and origins, the involvement with memory and identity, the relationship of people to space.

Linda Reif’s Valley Of Hinnom (2015) engages with a place that is steeped in history. Her series of 12 square, black-and-white photographs show the nature of Ge-Hinnom, a deep and narrow valley at the foot of the old city walls of Jerusalem – a place in “no man’s land”. The photographs show forms and structures which are more or less indistinct and out of focus. This impression is created by Reif by using out-of-date black-and-white films and a cheaply produced Chinese camera with a plastic lens. Even without the knowledge that this place is well-known for its bloody history – e.g. children were sacrificed to the heathen god, Moloch – one feels in these details an abandoned, deathly still landscape and, because of the black-and-white surface, something mystical, oppressive – one feels death. The landscape functions as a projection surface for history and is also closely tied up with new bloody events in the Israeli/Palestinian conflict/war. Reif’s photographs show just how much more impressive bearing silent witness to historically burdened places can be instead of talking about them.

Benedek Regös considers his photographic work, Genius Loci (2012), to be an attempt to place photographic work processes in the context of evidence, meaning, memory and topography. He examines the phenomenon that documentary photography, by capturing and concentrating on “unnoticed” details, “ennobles” too many objects and situations. In his work he tries to engage with this by photographing apparently unimportant and commonplace locations which are significant only because of a past event. In order to do this he first chooses archival photos which show the site to be where a prominent person was at the time of the shot and which has not changed in the meantime, thus allowing it to be documented. The unchanged nature of the location is thus critical because it has survived in a material sense (like the image) and we can see it as a physical and still accessible link between us and the person in question. Locations can be found with the aid of coordinates, thus becoming “inofficial monuments” of personal memory.

Petra Noll, for the collective