Opening: Monday, 21 November, 7 p.m.

Introduction: Ruth Horak

Finissage and catalogue presentation:

Friday, 13 January, 7 p.m.

sponsored by: BKA Kunst; MA7-Kultur; Cyberlab; Bezirkskultur Alsergrund

cooperation partner: Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Photography and light are as closely connected as telephones and sound. Light is not only a precondition for every photographic image and respectively manifested in the name of the medium, it is also responsible for the decisive developments in the area of photography. However light neither was, nor is, just the precondition for making a photograph but also always a challenge too. And, in the area of art in particular, where reference is often made to the surrounding circumstances of the medium, light is one of the many-sided components of photography that encourage reflection. In the FOTOGALERIE WIEN’s special focus for this year light is once again the actor at the centre of our attention.

In the three exhibitions, Light Experiments, Light Spaces and Light Qualities it plays both an ideal and formative role – light as a phenomenon, as the contrast with darkness, as a subject and a motif and also its influence and direct effect on what is depicted and the materials employed. How can light be fixed and rendered visible? How can it be installed in a space? What qualities of light are we talking about? Which sources? Temperatures? And how subjective is our perception in comparison to what the equipment records?

Henry Fox Talbot appended an important coda to photography: it was, he said, a self-image of nature that ‘was obtained by nothing more than the mere action of light’. In the third part of the exhibition series, Light, this is taken – at least in part – quite literally. Light with its incredibly atmospheric qualities becomes the main actor – moonlight or sunlight, the effects of the sun’s position and season, artificial light sources or light as set decoration. Light, light source, position, movement, changing colour temperatures etc. are all registered in scientifically experimental or subject-specific documentary, often using an analogue photographic recording system. In this context it is important to note that all contributions use the physical and chemical processes of analogue photography i.e. light sensitive film or paper which is exposed (sometimes with long exposure times) in order to invest light with a body. The camera which is used as intermediary functions as a substitute for our eyes which would miss all these qualities of light because they are protected by chromatic adaption (white balance) or an instinctive looking away if it becomes too strong.

Veronika Burger’s multi-part set consists of a video, a double slide projection, curtains, photographs, reproductions from books and, most importantly, two standard lamps with blue shades. The installation orbits these two – even if the lights go out, there is still light. Originally commissioned in 1987 by the Viennese lampshade maker Elisabeth Kemeter, the two lamps were supposed to appear on the Vienna set of the James Bond film “The Living Daylights”. They were completed and delivered but do not appear in the final version of the film. Burger tells the story of this commission, interviewed the lampshade maker and re-ordered the two shades. Reconstructed from memory, they are from now on at the side of historical documents and descriptions as part of the reconstruction of an event that can only be confirmed by the memories of the participants.

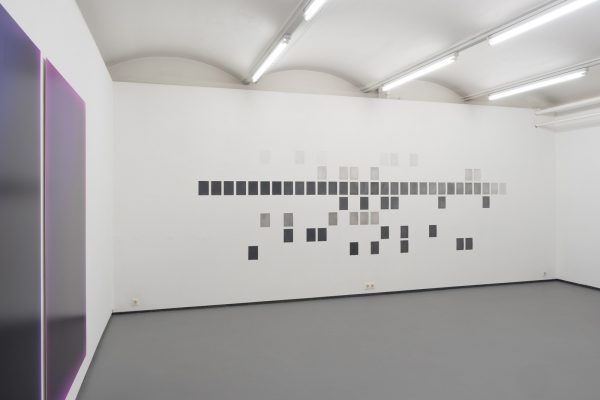

Victoria Coeln’s chromogrammes result from time-consuming darkroom work. She has been interested in colour phenomena and theories of colour for a considerable time and experiments with the basic colours of light, filters and multiple exposures. She has also been observing the interplay of light and colour in numerous serial exposures. The vibrancy of the chromogrammes derives from the sheets of glass painted with Reprolux transparent colours which she places in the enlarger instead of a film negative. One of the colours that Victoria Coeln finds particularly fascinating is magenta. Since it is not a spectral colour but an additive mixture of red and blue, the name for it only begins to become widespread in the mid-nineteenth century. Colour spaces that are imbued with particular depth and saturation open up through the superimposition of up to five layers of exposure with different intensities of coloured glasses, the intermediate processes (painting and photogram) and a degree of blurriness.

Inge Dick is well known for being able to liberate an infinite number of colours from a white wall. Since the 1990s a simple white surface serves her as a stage on which daylight in all its nuances and intensities performs. Ignored by lazy eyes, the camera undertakes to see the differentiations in the colour nuances that settle on this surface during the day – between sunrise and sunset – deep midnight blue to bright midday white. Filmed over three days and then cut into short chronological sequences that make it possible for our eyes to make comparisons and inscribed with exact time signatures, white slips into an infinite number of roles. In the “Jahreszeitenzyklus” [Cycle of Seasons] the fluctuations in daylight in our temperate zones or the temperature of the light in spring, summer, autumn and winter are rendered visible.

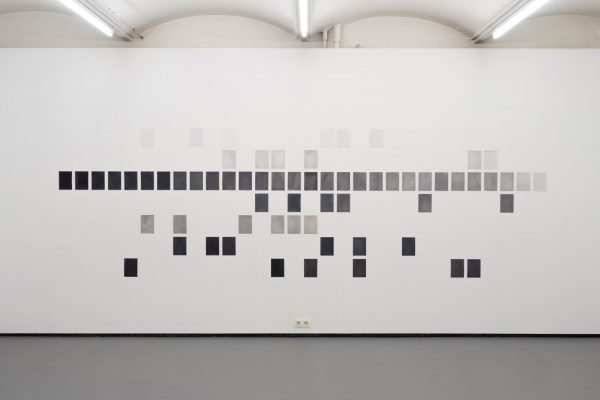

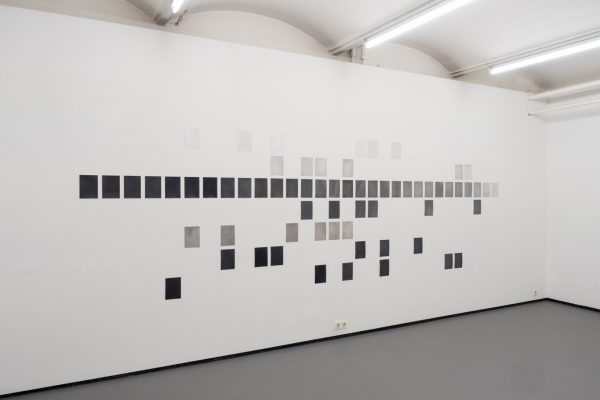

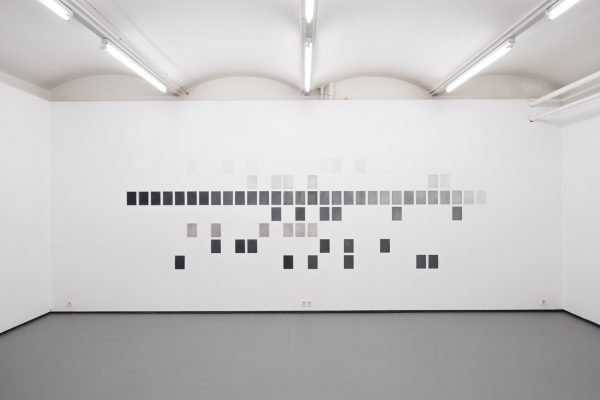

Sarah Hablützel from Switzerland exposed, or caused to be exposed in Hamburg a sheet of photo paper for 30 seconds each day for a whole month from 22 November to the shortest day of the year, 22 December. Following the same procedure, though not daily, she did the same in New York, Helsinki, Oslo, Singapore, Tokyo and Zurich. The resulting 66 luminogrammes, including raindrops, are given coordinates – in the titles – and hung in a corresponding grid. In this way, the 74° 0′ West – 139° 46′ East extension of the shooting locations and their different light intensities as well as the decreasing daylight (caused by the changing inclination of the earth’s axis) are also demonstrated in the exhibition space.

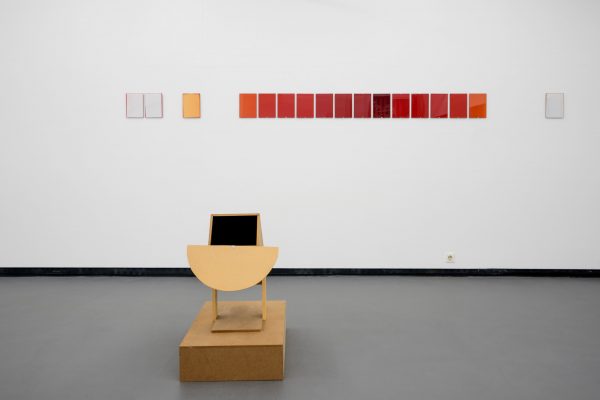

Ulrike Königshofer built a special apparatus to make Sechs Sekunden Mondlicht [Six Seconds of Moonlight]. Once again the analogue processes and thus the interplay of time and light or the most unhindered and direct depiction of a natural light source take centre stage. The 15 monochromes document the moonlight of a lunar cycle between 20 February and 14 March 2015, weather permitting. As matter-of-fact as her approach and interest in scientific methods are on the one hand, the results are nevertheless atmospheric, the yellows, oranges and reds that allow us to experience moonlight in a different form for once.

‘36 shots in 36 days, each a 24 hour exposure with an open shutter’, read the details of Michael Michlmayr’s contribution. This maximum exposure to light in March of 2016 was a challenge to the photochemical process – on the one hand to get any image of the world out there at all, given the long exposure times and, on the other, to capture the sun itself even if that was mainly in the form of burn marks. The extreme over-exposure led to the auto-development of the negative material so that the film only had to be fixed and washed in water. The slanted “cut” that the sun left on the film is the form of the course of the sun, its changing position and intensity during a clear day. The overlapping of these light trails provide a reference point for the “movement of the landscape” during those 36 days and thus a visualisation of the progression of time and space.

Exposures, a series by Günther Selichar which has 11 parts altogether, shows format-filling close-ups of lamps in the sense of video and film camera built-in permanent lighting or external studio lights that are synchronised with capturing devices. As with Selichar’s series, Screens, cold, these “tools” of photography, video and film are portrayed in a factual and documentary way with no differentiation made between small LEDs and large bulbs. Here, as with Inge Dick, the eye also resists – this time looking directly into the light which is set to its brightest. It is only in the photo that we are able to observe the form of the bulb and the diffuser discs. The thematic levels come together in the English term “exposures”: recording images, a state of being unprotected, radiation, revelation but – also quite literally – the film exposure, where the light inscribes itself into the sensor.

(textual support: Ruth Horak)