Opening: Monday, 11 June at 7 p.m.

Introduction: Katharina Manojlović

Finissage and Presentation of the Catalogue of the main focus COLLAGE:

Thursday, 12 July, 7 p.m.

sponsored by: BKA Österreich; MA7-Kultur; Cyberlab

Thanks to: WUK – Bereich Bildende Kunst: for providing a studio; WUK-Bereich Werkstätten; Werkstätte für Holz und Design; especially: G. Brandstötter, Kulturabteilung der Stadt Wien (MA7) – project sponsoring

Dadaist and poet Tristan Tzara called the invention of the collage the most revolutionary moment in the development of painting and meant by that the fundamental break with established forms of artistic representation that it symbolised. Implicit to the technical processes of what comprises collage — gluing (Fr. coller), scratching, cutting, tearing, folding, mounting, assembling and de-composing etc. is the potential for radicality. While the papiers collés of the Cubists drew their sustenance from used, discarded and apparently banal sources, we are surrounded today with multiply reproduced, re-formatted and re-edited copies of constantly accumulating digital debris. The current focus of the Fotogalerie Wien will present four exhibitions and includes a wide spectrum of methods and processes used in collage in contemporary photo and video art. This renders the narrative and autopoietic strengths of this art form visible along with its innovatory energy as one of its fundamental and most evident characteristics, especially in relation to new technologies or spatial and sculptural expansions. The drift of the images is also always guided by energies that are anarchistic, driven by chance and play.

The last exhibition of the COLLAGE special focus is a confrontation with two artistic positions which, despite all the differences in the mediums employed, are linked by an interest in a multi-media exploration of space from a social and cultural point of view as well as issues relating to perceptual theory. How much does the (non)simultaneous order of processes and (historical) events have an effect on their representability? What are the mechanisms and conventions that guide our perception? In the works of both Larcher and Pamminger the very smallest of shifts in perspection work to destabilise our way of seeing and alter meaning. Their spatial (de)constructions represent an order whose parts should not be simply read as representations of, for example, the external world, but as being subject to their own grammatical rules: Artificial languages that draw on reality and its media transformations, compress it and thereby create endlessly propagating (mental) spaces.

In Claudia Larcher’s work spaces are reconstructed, energised, remembered. Larcher’s video works can be understood as explorations of living spaces though less in the form of real places and much more in the sense of topoi, culturally moulded ways of seeing. Consequently her analyses are explorations of spaces and their representations in the media, traces of what those potentially evoke in us. In the video Baumeister (2012), the camera scans technoid infrastructures, architectural forms are traced in moving images. Here it is the spiral that lies at the symbolic heart of a building, the ORF studio in Dornbirn designed at the beginning of the 1970s by Gustav Peichl. The accompanying soundscape awakens associations and visions of the weightlessness of space and it is unclear who is moving, the room or us as viewers. Likewise in the film, Collapsing MIES (2018), picture fragments set in motion appear to be both familiar views and illusions at the same time – as a transparent panorama and undergrowth. Taken from architectural magazines these photo fragments all allude to buildings of Mies van der Rohe, whose reduced formal language of architecture is dissected by using montage techniques and is thus put under more careful observation. In SELF (2015) we eventually see shots of bodies – the camera travels across expanses of human skin in close up – images that may evoke reminiscences of Maria Lassnig’s experimental film Iris (1971) in which a female body is liquefied in the projection surface of various mirrors so that formations of flesh of grotesque appearance encounter one another. In the case of Larcher’s piece, it is the soundtrack alone, the body noises, that tell of someone’s presence. Here, too, the skin as the physical limits of the body is blurred into surreal landscapes.

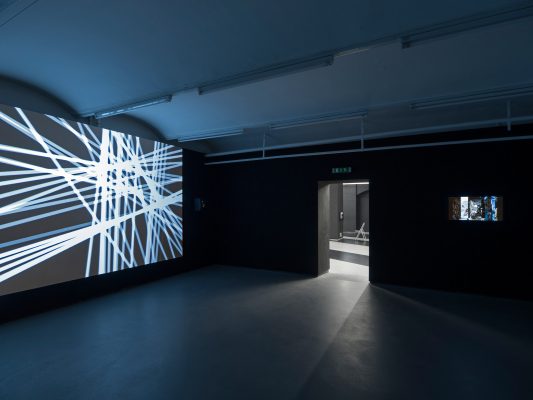

Klaus Pamminger´s installation, Shadow in the Cube, that he conceived specially for this exhibition, comprises filmic, photographic and sculptural collages. Its framework consists of illusionistic shadows inscribed throughout the gallery space. These cut through the white cube which then becomes a walk-through puzzle picture. The sculpture that can be seen in the exhibition space, Stiegenhaus, 11 Square Albin Cachot, 75013 Paris-13E / RC01-BDJ (2018) marks the highest degree possible of spatial abstraction while at the same time spatialising a fiction. What we see are the construction lines that Pamminger took from the film Belle de Jour (1967) – derived from the staircase that Séverine Sérizy (Catherine Deneuve) climbs in order to leave her old life behind. In the corresponding film works they become the signal of a structural rupture. On a sensory level, the concrete haptic perception and play of colour of the wall sculpture correlates with the audible click-clack of the heels of Séverine’s shoes. In Pamminger’s video work this sound, which ultimately is visually only accompanied by empty rooms, offers the sole possible orientation. The Fotointarsien begun in 2007, blur the borders between representational reality and fictional surface. The term Intarsien is normally associated with inlay work, in Pamminger’s case they are media set pieces that inscribe themselves into the architecture, image fragments from cinema films that the artist collages in photographs of his living space. This process creates greatly compressed pictorial spaces that unify different times. Also in the video work, Mackey vs. Film (2013), different space/time realities mutually populate each other: the US American Civil War period is transported by Gone with the Wind (1939), that of National Socialism by Gustav Ucicky’s film Mutterliebe (1939) – shot in Vienna – and the concrete time of Pamminger’s film material of the Mackey Apartment House built in 1939 by the Viennese-born architect, Rudolph M. Schindler, whose imagination, one might say, forms the (historical) link. In the same year that propaganda film, Mutterliebe, was shot in Vienna, Schindler may have seen Gone with the Wind. In making the simultaneity of non-simultaneous cultural formations visible, Pamminger leaves linear narrative methods behind.

(textual support: Katharina Manojlović)

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

INFORMATION

Renate Bertlman will be the first Austrian female artist to be represented with a solo show at the Austrian Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale. We are delighted and would like to express our warmest congratulations!

Renate Bertlmann at FOTOGALERIE WIEN / art exchange FOTOGALERIE WIEN:

1983 Neue Fotografie aus Wien

1985 Wiener Fotografie – Subjektives

1994 Der Molussische Torso (Projekt: Palme/ Richtex)

2002 Werkschau VII: Renate Bertlmann – Arbeiten von 1976–2002

2003 Austrian Photography – Korrelationen:

Northern Photographic Centre, Oulu und Peri,Centre of Photography, Turku, Finnland

2008 Themenschwerpunkt Liebe, Teil III – Scheitern

2008 Werkschau XIII: Intakt – die Pionierinnen